- Area: Siem Reap Province > Krong Siem Reab > Sangkat Nokor Thum

- | Type: Ancient Remains & Temples

[Updated 2024] – Originally recorded as Nagara Jayasri (holy city of victory), Preah Khan is a large and grand ancient temple at Angkor Archeological Park, Siem Reap. It was built in the 12th century under the reign of King Jayavarman VII (reign 1181-1218 AD) to honour his father, who built the nearby Ta Prohm to honour his mother. It is one of the must-visit temples in Angkor.

Located north of Angkor Thom, Preah Khan is on an intentional central axis with the Jayatataka Baray, Neak Pean, and Ta Som all once being hydraulically linked. Not just a temple, from all indications the 56ha site was a royal city that once housed hundreds of wooden buildings for monks, students, and workers inside its outer enclosure wall (700m x 800m), while the much smaller third enclosure (165m x 215m) contains the principal religious temple likely only accessed by royalty and their gurus.

Today, of course, we can access that third enclosure with two more enclosures plus a maze of chapels, courts, halls, and pavilions with a central shrine on the north-south east-west axis.

Visiting Preah Khan

The site is open from 7:30 am to 5:30 pm and the recommended visiting time is 1.5 to 2 hours although temple buffs could easily spend much longer and likely want to make repeat visits. No matter how many times you come here, you’ll always spot something new.

You can enter from the West, North, or East gate. You cannot enter by the South gate, more on that later. Across from the west entrance are restaurants and drink stalls, and also newly built toilets. After entering and crossing the moat on the west entrance, there is a visitor centre well worth a quick stop to check out the displays for some background info on the site. Alternatively, you can enter via the eastern gate, the traditional entrance, which also features a long bollarded causeway leading to the landing/terrace of the Jayatataka Baray from which the king and his consorts/subjects would have sailed across to enjoy the healing ponds and sacred waters of Neak Pean.

Highlights at Preah Khan are numerous and along with those I’ll include some of the hidden quirks for you to seek out

- The jetty of the Jayatataka Baray and the processional way on the eastern entrance

- The naga bridges and the hidden bas-reliefs underneath

- The 2.5m tall stone garudas that line the outer wall

- The “firehouse” inside the outer wall from the eastern entrance

- The stone Dvarapalas (swordsman) guarding the entries

- The Hall of the Dancers and its pediments

- The unique narrowing doors as you head in towards the central sanctuary

- Central sanctuary and the amazing acoustics of the surrounding chambers

- The amazingly ornate inside wall of the eastern gopura

- The two-story round pillared structure, unique in the ancient Khmer architecture, is revered as the rice harvest prayer hall

- The revered bass relief that some believe to be a Queen, in a hidden chamber to the west of the central north-south axis

- The restored buildings in the north-west and south-west quarters inc. the wall of ascetics on one of the small shrines.

- The circular floral patterns that are ubiquitous, yet, randomly contain carvings of mythical creatures, people, and animals.

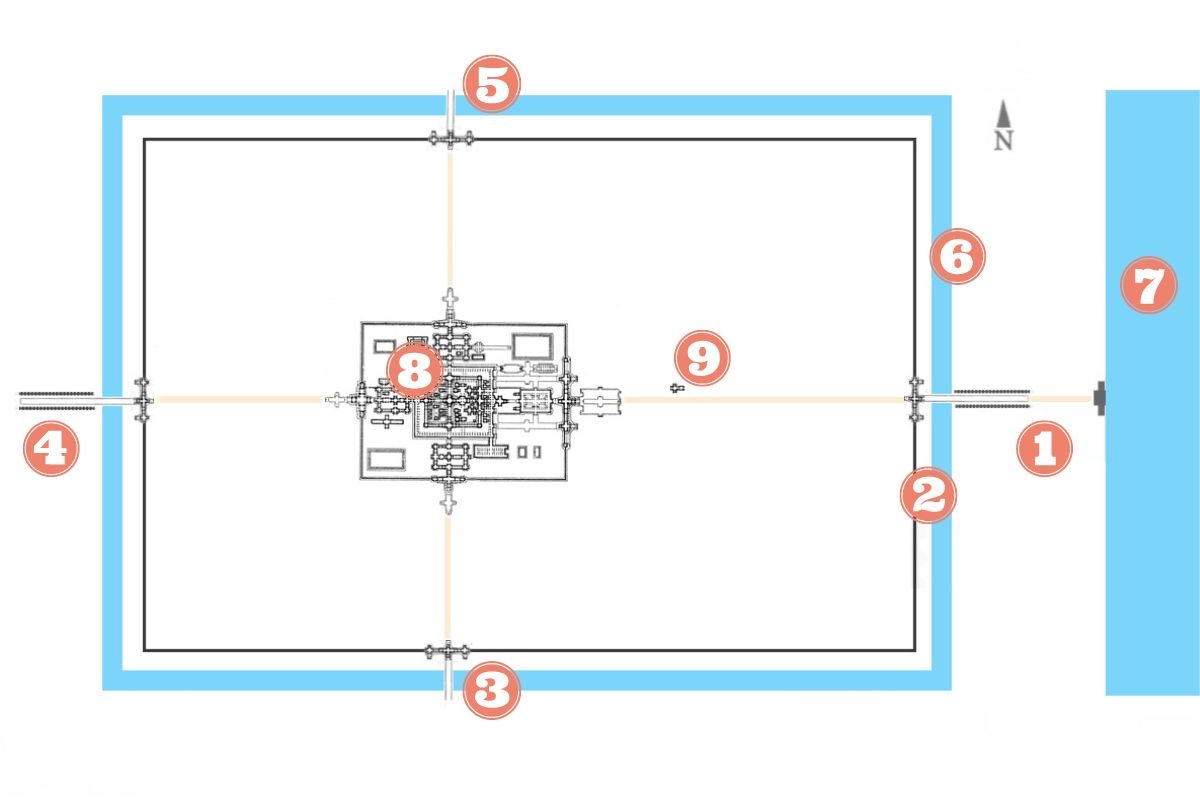

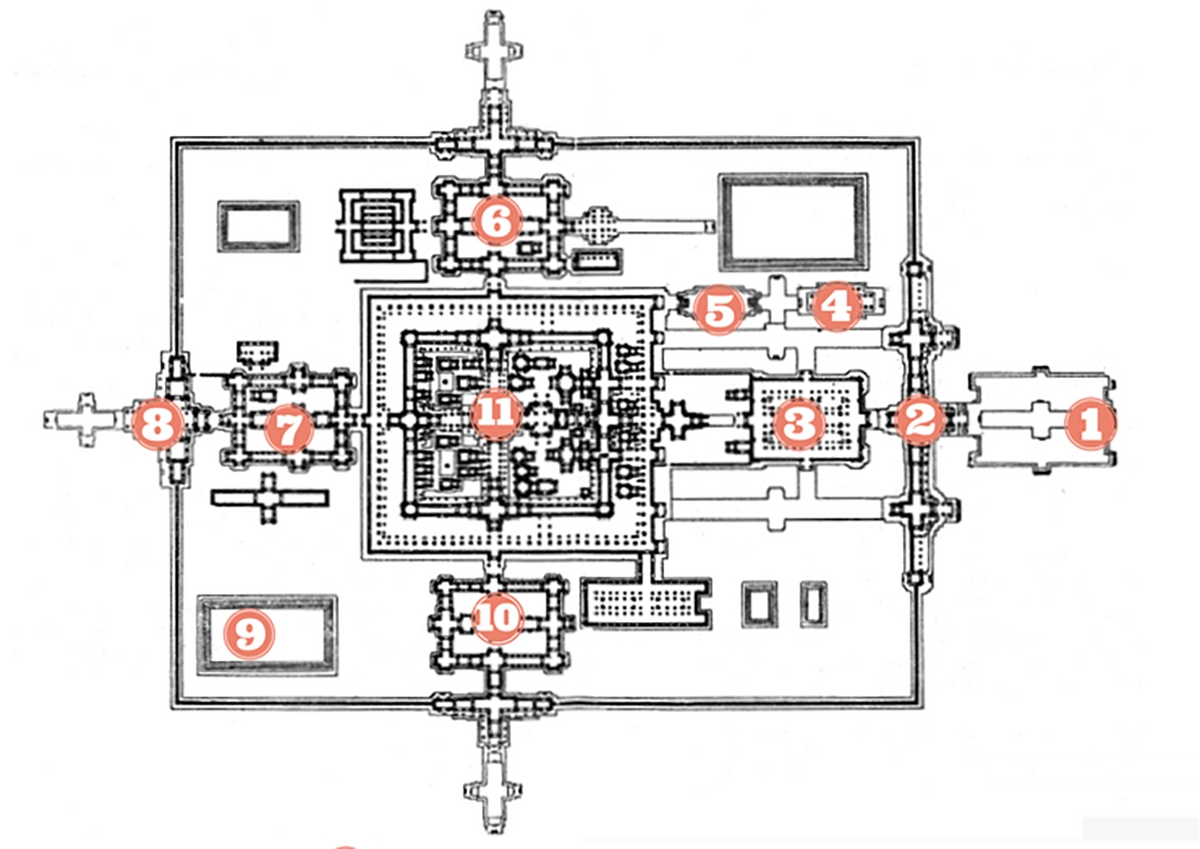

Preah Khan Layout Map

Overall site plan and on the right, temple proper, inside the third enclosure.

The outer wall of Preah Khan is of laterite and bears 72 garudas holding nagas, at 50 m intervals. Surrounded by a moat, it measures 800 by 700 m and encloses an area of 56 hectares (140 acres). Connecting with the eastern entrance of Preah Khan is a landing stage on the edge of the Jayatataka baray, which measures 3.5 by 0.9 km (2 by 1 mi). This once allowed boat access to the temple of Neak Pean in the centre of the baray.

As usual, Preah Khan is oriented toward the east, so this was the main entrance, but there are others at each of the cardinal points. Each entrance has a causeway over the moat with nāga-carrying devas and asuras similar to those at Angkor Thom. Often missed, these causeways also feature bas-reliefs on each side, often covered by the water.

Inside the outermost (or 4th) enclosure is a vast forested expanse that was originally occupied by the city; as this was built of perishable materials it has not survived although archaeologists have been able to make several discoveries relating to that habitation. Halfway along the path leading to the third enclosure, on the east side, is a Firehouse/House of Fire (or Dharmasala/Vahnigriha) similar to Ta Prohm’s.

The third enclosure wall is 200 by 175 metres (656 by 574 ft) offering entrance pavilions (gopura) at each cardinal point. In front of each gopura is a small cruciform terrace with entrances flanked by guardian lions and Naga balustrade whilst the main eastern entrance features a monumental terrace. These gopura are notable for their impressive reliefs in the pediments and gargantuan sandstone Dvarapala guardians flanking the doorways as best seen on the west gopura.

Heading west from the eastern gopura, along the main axis, is a Hall of Dancers. The walls are decorated with Apsaras/dancers; Buddha images in niches above them were destroyed in the supposed anti-Buddhist reaction under Jayavarman VIII.

North of the Hall of Dancers is a two-storeyed structure with round columns. No other examples of this form survive at Angkor, although there are traces of similar buildings at Ta Prohm and Banteay Kdei. It is speculated that this may have been the Harvest Prayer Hall. Nearby is a laterite platform, also unique, featuring stairs at its east and west end which are flanked by guardian lions. It is speculated to have once housed the sacred sword, the very object that gives Preah Khan its contemporary name.

Occupying the rest of the third enclosure are ponds in each corner, and satellite temples to the north, south and west. While the main temple was Buddhist, these three are dedicated to Shiva, previous kings and queens, and Vishnu respectively. They are notable chiefly for their pediments: on the northern temple, Vishnu reclining to the west and the Hindu trinity of Vishnu, Shiva and Brahma to the east; on the western temple, Krishna raising Mount Govardhana to the west. Wandering through the labyrinth of halls, the remains of a large standing Buddha can be seen along with numerous decorative lintels, and occasionally, pediment reliefs that were covered by its own later additional construction phases.

Connecting the Hall of Dancers and the wall of the second enclosure is a courtyard containing two libraries. The second eastern gopura projects into this courtyard; it is one of the few Angkorian gopuras with significant internal decoration, with garudas on the corners of the cornices. Buddha images on the columns were changed into hermits under Jayavarman VIII.

Between the second enclosure wall (85 by 76 m) and the first enclosure wall (62 by 55 m) on the eastern side is a row of later additions that impede access and hide some of the original decoration. The first enclosure is choked with ruinous buildings. The enclosure is divided into four parts by a cruciform gallery, each part almost filled by these later irregular additions.

The walls of this gallery and the interior of the central sanctuary are covered with holes that some believe are for the fixing of bronze plates. While corrosion from metal pins can be seen in the outer halls, the inner sanctuary holes have traces of stucco.

Inside the central sanctuary, at the very centre of the temple, is a stupa that is debatable as to whether it was the original object of worship in the temple, perhaps replacing a statue of Lokesvara, or whether it was added under a later king in the 13th century, or even later in the post-Angkorian period. Being an object related to Theravada Buddhism, and quite similar to those seen in Sri Lanka, some consider it may have been added post-Jayavarman VII at least.

Hidden away in a chambered area adjacent to the central shrine is a room that features a very special bas-relief carving of what is today revered as one of Jayvarman VII’s queens.

The Bridges, Moat, Outer Wall, and Garuda Walk

Often unexplored as most visitors head into the more fascinating inner sanctum of the temple, Preah Khan has extraordinary bridges, outer walls lined with Garudas (mythical birds), and detailed gopuras (gates). After crossing the moat, take care to look at each side of the bridge for the bas-reliefs hidden underneath, follow the wall in any direction, and take a walk around the outer wall and moat. Every 50m you’ll come across a Garuda statue in varying states of restoration or decay along with the character of the often ruinous and leaning wall. The corner Garudas are especially interesting. The southern gate and bridge of Preah Khan are rarely visited and have that “jungle find” feeling having never been touched by restoration works. Read more about the Garuda and the outer wall of Preah Khan

Preah Khan History

Preah Khan was built on the site of Jayavarman VII’s victory over the invading Chams in 1191. Unusually the modern name, meaning “holy sword”, is derived from the meaning of the original—Nagara Jayasri (holy city of victory).

The site may previously have been occupied by the royal palaces of Yasovarman II and Tribhuvanadityavarman.

The temple’s foundation stele has provided considerable information about the history and administration of the site: the main image, of the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara in the form of the king’s father, was dedicated in 1191 (the king’s mother had earlier been commemorated in the same way at Ta Prohm). 430 other deities also had shrines on the site, each of which received an allotment of food, clothing, perfume and even mosquito nets; the temple’s wealth included gold, silver, gems, 112,300 pearls and a cow with gilded horns.

More than a temple, it was an institution that combined the roles of city, temple and Buddhist university. The stele inscription also notes that there were 97,840 attendants and servants, including 1000 dancers and 1000 teachers.

Inscriptions

Via CIK

- K. 462 – (K. 638/K. 639) – 17 Khmer inscriptions – Cœdès 1951, p. 107, p.114

- K. 463 – BEFEO XII (9), p. 186

- K. 621 – central passage connecting gopuras I and gopuras II – 2 lines of Khmer text – Cœdès 1951, p. 109

- K. 622 – central passage connecting gopuras I and gopuras II (doorjamb) – one line of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 109

- K. 623 – east gopura IV, north side porch – four lines of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 112

- K. 624 – cloister R, east gopura door – one line of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 113

- K. 625 – cloister R, door to the south of the central gopura – Cœdès 1951, p. 112

- K. 626 – cloister R, south-west corner – five lines of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 112

- K. 627 – cloister T, gopura east – four lines of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 115

- K. 628 – cloister T, gopura south – four lines of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 115

- K. 629 – cloister T, gopura south – five lines of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 115

- K. 630 – cloister T, angle northeast – four lines of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 115

- K. 631 – cloister T, angle southwest – five lines of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 115

- K. 632 – aedicula S. gopura northeast, south interior door – one line of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 114

- K. 633 – aedicula S. gopura southeast, north door – one line of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 114

- K. 634 – west central S. gopura aedicula, west door – one line of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 113

- K. 635 – aedicula S. gopura north-west, south door – one line of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 113

- K. 636 – aedicule S. gopura south-west, north door – one line of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 114

- K. 637 – aedicula S. central east gopura, west door – three lines of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 114

- K. 638 – aedicula D [south] of enclosure I – two lines of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 107

- K. 639 – aedicula H1 [north] of enclosure I – two lines of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 109

- K. 640 – aedicula P of enclosure I – two lines of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 108

- K. 641 – aedicula P [south] of enclosure I – two lines of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 109

- K. 642 – gopura IV east, south entrance – four lines of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 112

- K. 644 – gopura III east, north wing – labelled as graffiti

- K. 779 – on a conch holder (in PP Museum) – Soutif 2008

- K. 906 – cruciform building enclosure II East – four lines of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 111

- K. 907 – numerous – Cœdès 1951, p. 107

- K. 908 – gopura I Est – four-sided stele with seventy-two lines of Sanskrit on each side – Cœdès 1941

- K. 914 – gopura I north – two separate lines of Khmer – Cœdès 1951, p. 111

- K. 1114 – one line of Khmer

- K. 663, 671, 901, 916 and 951 are labelled as graffiti

References and Further Reading

- Soutif Dominique. La monture de conque inscrite du Musée national de Phnom Penh Relecture de l’inscription angkorienne K. 779. In: Aséanie 22, 2008. pp. 47-61.

Map

Site Info

- Site Name: Preah Khan Khmer Name: ព្រះខ័ន

- Reference ID: HA11701 | Last Update: November 18th, 2024

- Date/Era: 12th Century

- Tags/Group: 12th Century, Angkor, Angkor Grand Circuit, Jayavarman VII, Map: Angkor's Top 30 Temples & Ancient Sites, Map: Top 100 Temples & Ancient Sites (Siem Reap), Temples

- Location: Siem Reap Province > Krong Siem Reab > Sangkat Nokor Thum

- MoCFA ID: 417

- IK Number: 522

- Inscription Number/s: K. 462, 463, 621, 622, 623, 624, 625, 626, 627, 628, 629, 630, 631, 632, 633, 634, 635, 636, 637, 638, 639, 640, 641, 642, 644, 663, 671, 779, 901, 906, 907, 908, 914, 916, 951, 1114